On a day which sees the Parmalat heat being turned up to full blast, with a looming 'cara a cara' between former Chief Financial Officer Fausto Tonna and Parmalat chief legal counsel Gian Paolo Zini, and while in the United States a class action law firm has named investment bank Citigroup Inc and auditing firm Deloitte & Touche Tohmatsu among defendants in a lawsuit against the food group - a lawsuit incidentally filed on behalf of a U.S. pension fund (oh when, oh when will we get class action lawsuits here in Europe) - on such a day it might well be worth asking ourselves one simple question: is this just another one-off scandal?

You see the easy course of action here is to simply shrug your shoulders and say: well the US had Enron, now we got Parmalat, so what! And in part you would be right. (Interesting detail how yet another of the big Marquee accounting names is stuck right in the middle, they must all now really have earned themselves a reputation for 'quality'). I mean, after all, isn't the word from the other side of the pond that virtually nothing has happened, that everything has been taken in its stride. Well yes, and no. I think sometimes we can get too cynical, and cynicism normally breeds complacency, which in the end just defends the status quo.

Anyway, our focus should definitely be on this side of the water, on what is happening here and now, and what kind of response we are seeing. Well, Italy has

hurriedly amended its bankruptcy laws - apparently to 'safeguard' jobs, although what that might mean in this context is anyone's guess. The Italian government has also been pressuring Brussels to waive rules on state aid (and in a way it's difficult to see after Alstom how they can turn a deaf ear to the plea for help, I mean what we have seen time and time again is a Commission breathing fire and

then turning 'flexible' so there seems little reason to imagine that this is going to change: the ECB is another box of tricks altogether, and I have a forthcoming euro post which will touch on this).

In my mind the oustanding question here is not how Parmalat could have happened, but whether the Italian state itself is simply one big Parmalat. When the FT reporter tells us that a spokesman for Mario Monte was of the opinion :

"

that, in light of our May 2000 decision, the measures adopted by the Italian government will not contain fiscal advantages which put state resources at risk," we might well ask why state resources will not be put at risk. The reason, I suspect, would be because of some rather dubious off-balance-sheet practices, rather like the so-called 'one-off measures' which have enabled Italy to avoid technically breaching the 3% deficit limits from time to time. What really would be interesting here would not be merely an investigation of the Parmalat problem, but rather an independent audit of the entire Italian public finance structure.

You think I'm joking? I'm afraid I'm not. Of all the eurozone states, the Italian one has the financial system which is most likely to default first. Public debt is already over 100% of GDP, and to this you need to add all the private debt accumulated in recent years if you want to get a true picture of Italy's vulnerability.

Speaking to a Brusssles conference on European ageing held in March last year, EU economics commissioner Pedro Solbes

had this to say:

"

Our conclusions are worrying. On the basis of current polices, a clear and unequivocal risk of unsustainable public finances exists in at least half of EU Member States".

Well if such conditions exist in at least half of the EU states, then surely Italy will be in the forefront of the defaulters. An index of vulnerability risk presented at the

same conference placed Italy in 11th place out of twelve countries considered (with only Spain in a worse position), and had the following to say:

"

The high vulnerability group includes three major continental European countries that all face a daunting fiscal and economic future: France , Italy, and Spain. Their poor Index scores can be attributed, in varying degrees, to severe demographics, lavish benefit formulas, early retirement, and heavy elder dependenceon pay-as-you-go public support. It is unclear whether they can change course without severe economic and social turmoil. Italy has scheduled big reductions in future pension benefits, but only after grandfathering nearly everyone old enough to vote. France and Spain have yet to initiate any significant reform of elder benefit programs.......Italy has scheduled deep cuts in future benefits that raise its public-burden rankingbut only at the expense of impoverishing its future elderly".

And it isn't only on public debt and ageing that Italy scores badly: productivity improvements are notoriously amongst the lowest in the EU, uptake on the internet (unlike the mobile phone) is comparatively low, and where oh, where are all the Italian bloggers?

At another conference - this time on demography and replacement migration - held by the UN, it was argued that

maintaining the 1995 dependency ratio in Italy means:

"

A total of 120 million immigrants between 1995 and 2050 would be required to maintain this constant ratio, yielding an overall average of 2.2 million immigrants per year. The resultant population of Italy in 2050 under this scenario would be 194 million, more than three times the size of the 1995 Italian population. Of this population,153 million, or 79 per cent, would be post-1995 immigrants or their descendants."

Obviously immigration on such a scale is impossible to conceive of, but remember this was considered what was needed to maintain the relatively favourable conditions of recent years (when, I will remind you Italy has gotten itself into debt to the tune of over 100% of GDP). But this was assuming the rest of the world would remain the same, which we can now clearly see will not be the case. The rise of China and India means that global realingnment is about to happen, and this will worsen Italy's problems not improve them.

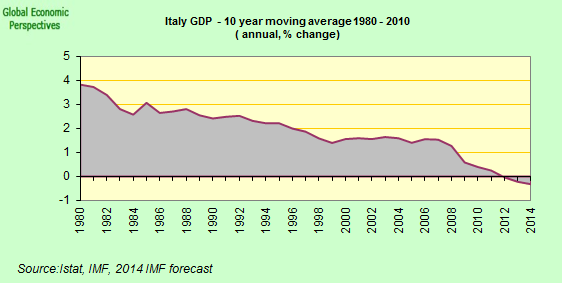

So, summing up, this is why Parmalat is more than just a scandal: it is a symbol of a society whose way of doing things has run into deep trouble. Reforming Italy was and should have been possible in the heady days of the 80's and 90's with a relatively young and stable society and the wind behind them. That todays Italians are ready, willing and able to do now what they have not had the strength to do before seems unconvincing to say the least. So I leave you with one thought: this last year the Italian economy struggled to achieve a growth rate of under 1%, are we witnessing the end of economic growth Italian style. Is what we have lying out there in front year after year of negative growth (or contraction) as a declining labour force, sub par productivity and increasing taxation of those in employment make job creation an ever more difficult process? Will young Italians one day be forced to leave their country in search of work to support their parents and grandparents just like those Bulgarians we presently have in our midst?